Guest blog written by Cara Myers

It was March of 2016 and the rains had completely failed for a second year in southern Mozambique. Farming families had no crops. Children were missing school to dig up river roots to eat. Teachers were sending students home because they were “too hungry to learn anything.” Even in normal years, child malnutrition and poor school participation are major issues in Mozambique. This is one of those big, complex problems that is caused by a myriad of interrelated causes and sub-causes that are difficult to disentangle and prioritize.

So there we were, myself, Talvina Ualane and Roberto Mutisse, all of us former colleagues who had worked together for a disaster relief nongovernmental organization in Mozambique in the past and felt deeply motivated to do something to help people affected by this crisis. But, where did we even begin?

We started with what we could do. This is one of the key aspects of the triple-A framework used in PDIA, which stresses that the space for change must include three key factors: authority, acceptance, and ability. PDIA also emphasizes moving to action quickly rather than taking a long time to try and plan everything out before starting to work. By deconstructing the problem into small, manageable bits, it creates points of entry whereby you can start addressing one of the causes or sub-causes of the problem and build the capacity to do more from there.

In our case, this meant figuring out how we could make a difference with the limited resources we had pulled together and our small team of three dedicated colleagues. We settled on a school lunch program because we thought it would draw two cards with one hand – provide kids the nutrition they need and get them back in school – but also because we thought it would be feasible for us to actually implement. There are a whole host of other interventions out there that can address child nutrition or education outcomes, but we had to think about what we had the authority and ability to do and what would be accepted by the local community. We received authority from the district-level Ministry of Education, signing an MOU. We also met with teachers and community leaders at the schools where we would start working, discussing our idea and getting them on board. All of this took over three months to get approved, which was frustrating given the urgency of the situation. But Roberto insisted that we needed to have the authority to do the work and he was right.

When Talvina, Roberto and I first launched the school lunch program in three primary schools, it was a six-week pilot project. We wanted to see if it would work logistically and create some of the changes we hoped for. We hadn’t formed an official organization or named it the “Mozambique School Lunch Initiative (MSLI)” yet. While we expected that the community would accept the program, this trial period would also allow us to get feedback quickly.

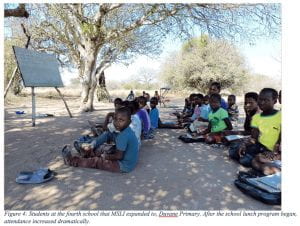

Within a month, the head teacher from a neighboring school came to Talvina and asked us to start the school lunch program in his school as well. He said that all of his students had started attending one of the three nearby schools that had a school lunch program instead. This seemed like strong anecdotal evidence that the school lunches were serving a real need and the acceptance sphere of our “space for change” was growing.

So we expanded to a fourth school and extended the program for another six weeks. A couple of months later, we realized we actually had enough traction that it was worth pursuing this program further and decided to officially incorporate as a non-profit organization. We still had a lot of work to do to refine our model and continue iterating, but now we had an indefinite time horizon. That provided the opportunity for us to move from focusing solely on the crisis brought on by the drought but to consider the underlying problems of child malnutrition in rural Mozambique as well.

When we started, we knew nothing about the Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) framework. But looking back now, I see that much of our success came from incorporating elements of the PDIA approach without knowing it. A year and a half after we started MSLI, I learned about PDIA through two courses at the Harvard Kennedy School and started applying more of its concepts directly with the MSLI team. Perhaps the best example of this was the launch the Seed Support program as part of the school lunch program’s procurement strategy.

The Seed Support program was first piloted as a direct response to one of the main principles of PDIA: local solutions for local problems. When the drought ended – nine months after we started serving school lunches – farmers started to ask us how they could get involved in the school lunch program. Week after week, they had seen MSLI cart in truckloads of food to their local school, including beans, vegetables, and chicken – all things that they could produce in their own farms now that the rains had returned. They wanted to partner with MSLI to grow the food crops needed for the school lunch program so that they could sell directly to our supply chain. But the drought had wiped out their stocks of seeds, so they needed support to start planting. The Seed Support branch of our program was born.

This idea emerged organically, but it still required careful consideration before we decided to move forward. We reassessed our “space for change” and realized that our work with the school lunch program over the last year had given us a foundation in the community, increasing our authority and acceptance. During this time, we had also deepened our understanding of the root causes of child malnutrition and were ready to tackle additional causes and sub-causes that were related to our overarching problem.

The rationale behind the Seed Support program was that MSLI would provide inputs for farmers to grow crops for the school lunch program directly, creating a local supply chain that would reduce our costs and provide a source of income for local farmers. Beyond this, we also saw the potential to leverage the school lunch program to address the underlying causes of child malnutrition – namely that farmers were not producing enough to feed their families. When we went through the Five Whys thought process used in PDIA, we came to the following:

Q1: Why are children dropping out of school or not attending regularly?

A1: Because they are hungry.

Q2: Why are they hungry?

A2: Because their families don’t have enough food.

Q3: Why don’t the families have enough food to feed their children?

A3: Because most families depend on subsistence farming and they are not producing enough.

Q4: Why aren’t they producing enough?

A4: Because they do not have access to the inputs to increase their yields, till more land, store their production during the lean season or access markets to sell their surplus and earn income to use to buy food during the lean season.

Q5: Why don’t they have access to these inputs etc.?

A5: Because most farmers are very poor and have no access to finance to purchase inputs. They live in rural areas far from markets and the transaction costs of transporting and selling their produce is very high.

While the school lunch program targeted the top two levels of the Five Whys, we believed that integrating the Seed Support program into our procurement strategy would expand our organization’s ability to holistically tackle the bottom three levels as well. Crucially, we also saw many advantages of these programs going hand in hand. I had seen examples of “home-grown” school lunch program models in other countries, such as Brazil, that connected large-scale public procurement programs to smallholder farmers. But the Mozambican context is quite different and in order to avoid isomorphic mimicry, we needed to experiment around what would work – learning by doing.

We started with beans and kale – two crops that the school lunch program used the most and were best suited to the local field conditions. The first season had very mixed results. At each of the four schools, ten farmers had self-selected into a group and received a starter kit of seeds to plant. One group prepared a communal plot of land and planted together, harvesting moderate amounts. Another group divided up the seeds and each member planted on their own farm, with very little production. The third group waited to plant their seeds until they saw the other two groups harvesting and earning money from their sales, then planted on a communal plot and harvested more than all the others. The fourth group cooked the bean seeds and ate them.

Ever since that first season, we have taken lessons learned and adjusted our strategies to yield greater success. We have also realized the extent to which learning was required on both sides, by the MSLI team and by the farmers, including building trust and demonstrating through example. In many ways, the variation in results and “positive deviance” of some groups in the first few seasons became an example for the others, leading to wider change and acceptance. After generations of doing things one way and seeing other NGO programs come and go, not everyone was willing to try things differently. But when some did and doubled their income, this motivated the others to give it a shot as well.

For us, this demonstrated the potential spillover effects of positive deviance and the fact that change does not happen uniformly at the same time. Through many iterations, we have been able to adjust our expectations, metrics of impact, and time horizons to better match the actual change process. Change in these contexts is not a linear process, and the PDIA framework has helped us better understand how to build on the small wins achieved in each iteration and the capabilities developed along the way.

As of September 2019, farmers are now harvesting the crops from the fifth iteration of the Seed Support program. They have grown beans, kale, tomatoes, onions, beets and sweet potatoes. Their production is now more than seven times what it was in the first season. Farmers have more food for their families, they’re earning income from MSLI and they’re even able to sell the remaining surplus to other families in neighboring villages. All of these things have contributed to improved child nutrition and increased school participation, which tie back to our problem-driven approach.

Additionally, when we realized that the Seed Support program would require much greater capacity development, we adopted a PDIA template to help us keep the team accountable and reflect on the progress, challenges, and opportunities for further growth. Each season is a natural iteration, but it is useful for us to have more frequent check-ins built into our management. At the end of each week, our team fills out a two-page document that includes the questions:

- What did you plan to do this week?

- What did you do this week?

- What did you not do this week?

- What did you learn this week?

- What was challenging this week?

- What do you plan to do next week?

This provides the basis for us to discuss progress and brainstorm how to address any issues that inevitably come up. This approach has been tremendously useful because it serves as a monitoring tool that allows us to take action in real time based on our reflections of what’s working and what’s not – referred to in the PDIA framework as tacit knowledge. Highlighting quick wins has also been very important to keep the team excited and motivated, because in the big picture, we have a long way to go.

In an ecosystem that is missing so much, it can be hard to know what to do, or it can feel like you’re never doing enough. The problem is huge, and it may be more than a decade before it’s actually “solved.” But by deconstructing the problem and focusing on addressing the causes and sub-causes, we are inching our way closer to real, transformational change. Currently, MSLI works in five rural primary schools in Mozambique, serving over 1,000 students every day and sourcing from 32 local farmers in the Seed Support program. This is PDIA at the grassroots, where we see each iteration as an opportunity to get nearer to our goal – a future where no child in Mozambique goes to school hungry.

Cara Myers is the Co-founder and Executive Director of the Mozambique School Lunch Initiative (MSLI). She learned about the PDIA approach by taking two courses at the Harvard Kennedy School as part of her Master’s in Public Administration in International Development (MPA/ID) program. She then began applying more of the concepts directly with the MSLI team. This is her PDIA story.

To learn more, visit our website or download the PDIAtoolkit (available in English and Spanish).